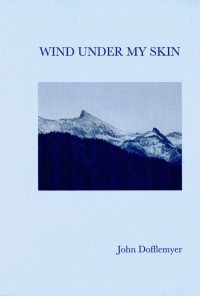

It’s habitual, looking to the mountains for our future, the Kaweah Peaks over Remy Gap in the southern Sierra Nevada above, not completely dressed in snow from the last storm on December 16th— another forecast for the 23rd. Ideally, the snow is laid in while it’s cold enough to freeze before mid-January, then slow melt to feed our rivers and replenish the groundwater in the San Joaquin Valley, once the most productive agricultural region in the world, or so I was told in college.

Much has changed since the 60s when Visalia was a town of 16,000. Now a city populated by 124,000 people drawing on groundwater resources year-round. The growth of Valley towns has also displaced some of our best agricultural ground in a short span of fifty years. The implementation of flood control structures on nearly every river on the west slope of the Sierras since, regulating surface water flows, have also had a severe impact to groundwater levels in the Valley. Add the wild cards of drought and more deep wells, less low snow as the climate changes, ours is not a hand to bet on long.

Well-meaning, but onerous, water legislation will not create more water. Nor will the monies set aside to build more dams, especially since we haven’t filled the ones we have in years. But for us, and most foothill livestock producers, we look to the Sierra snowpack this time of year for our future summer stockwater, the small leaks in granite cracks that feed our springs providing water for cattle and wildlife.

Share this: Dry Crik Journal